The Union Army refers to the United States Army during the American Civil War. The Union Army is also known as the Northern Army, and the Federal Army.

Contents

History of the Union Army

Secession and the Beginning of the Civil War

The United States was in crisis in 1861. Secessionist firebrands and radicals in the South had won out over the more moderate voices there, and secession was spreading like wildfire. By early April 1861, seven Southern states had already seceded from the Union, with four more threatening secession.

The states that seceded formed a new government, called the Confederate States of America. The Confederate government would not tolerate the presence of a “foreign force” on its territory, and they saw Fort Sumter as the presence of a foreign force (as its commanding officer and its men were still loyal to the Union), and on orders from the Confederate government, Confederate forces attacked the fort On April 12th, 1861. Fort Sumter surrendered the next day. The war had begun.

Formation of the Union Army

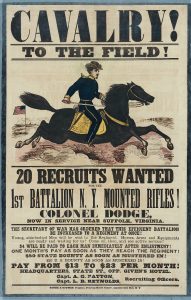

In April 1861, there were only 16,000 men in the US Army, and many of them resigned and joined the Confederate Army. Several hundred US Army officers even resigned to join the fledgling Confederate Army, among them Robert E. Lee, who had initially been offered the job as commander of the Union Army. Lee would become the commander of the Confederate Army instead). With a shortage of men and officers, and a state of open war, president Abraham Lincoln called on the states to provide 75,000 men for three months to put down the insurrection in the South.

At first, the call for volunteers was easily met (it isn’t difficult to find 75,000 volunteers in a country of over 26 million), but after the Battle of First Bull Run, it became evident that the Union Army needed far more men. Therefore, on July 22nd, 1861, Congress authorized a volunteer army of 500,000 men. Over the next four years, 2.5 million men would serve in the Union Army.

Leaders

Several men served as commanders of the Union Army throughout its existence, among them George McClellan, “Fightin’ Joe” Hooker, and George Meade. All of them were replaced for one reason or another. In March 1864, president Lincoln appointed Ulysses S. Grant General-in-Chief of the Union Army. Grant was the commander of the Union Army from then until the surrender of the Southern armies some 13 months later. Grant led the Union Army in delivering the final knockout punches to the Confederacy by decisively defeating the Confederate Army in many fierce battles in Virginia, eventually capturing the capital of the Confederacy itself, Richmond (something McClellan, Hooker, and Irvin McDowell, the original commander of the Union Army in the spring of 1861, had all tried to do and failed).

Grant had critics who complained about the atrociously high numbers of casualties that the Union Army suffered while he was in charge, but Lincoln would not replace Grant, because, in Lincoln’s words: “I cannot spare this man. He fights.” (a reference to what was viewed as the over-cautiousness that McClellan and others had displayed early in the war)

Union Victory

Grant’s decisive victories made sure that the Civil War ended with the unconditional surrender of the rebelling Southern states (northern newspapers of the day hailed U. S. Grant as “Unconditional Surrender” Grant), as opposed to a conditional surrender wherein the rebelling states would be allowed to have autonomy and keep slavery. Southern diplomats had been trying to negotiate conditional surrender since the decisive defeat that the Confederate Army suffered at Gettysburg, but President Lincoln and General Grant would not hear of it. Both men agreed that the Union Army would have to smash the Confederate Army in the field of battle, and stop the rebellion. Anything short of that would be a failure.

That goal was achieved on April 9th, 1865. On that day, Confederate Commander Robert E. Lee officially surrendered to General Grant at Appomattox Courthouse (the tired and beaten Southern forces had already been surrendering en masse to the Union Army for several weeks). That day officially marked the end of the bloodiest war in American history, the end of the Confederate States of America, and the beginning of the slow process of Reconstruction.

Casualties

2.5 million men served in the Union Army between its formation in April 1861 and the official surrender of Southern forces four years later. Of these, about 360,000 died in combat, from injuries sustained in combat, or from disease; and 275,000 were wounded. 1 out of every 4 Union soldiers was killed or wounded during the war. This is by far the highest casualty ratio of any war that America has ever been involved in (For comparison: In World War II, 1 out of every 16 American soldiers was killed or wounded. In Vietnam, 1 out of every 22 American soldiers was killed or wounded).

In total, 620,000 men died during the Civil War. This is made all the more devastating by the fact that there were only 34 million Americans at that time, so a full 2% of the American population died in the Civil war, 4% of the Male population. In today’s terms, that would be the equivalent of 5.4 million men dead. America has never had a war that was anywhere near this devastating, before or since.

Ethnic Groups in the Union Army

The Union Army was incredibly diverse. About 10% of Union soldiers were Black (although colored regiments did not see much combat), and about 25% of Whites who served in the Union Army were foreign-born.

Of the 2.5 million Union soldiers:

- 750,000 were German (216,000 were German-born). 30% of Union Army soldiers were German (9% were German-born). Robert E. Lee recognized that the Germans were such an integral part of the Northern Army. Lee said, “Take the Dutch out of the Union Army and we could whip the Yankees easily.”

- 370,000 (?) were Irish (150,000 were born in Ireland). 14% of Union Army soldiers were Irish (6% were born in Ireland).

- 210,000 were Black; about 8% of Union Army soldiers were Black. Half were freedmen who lived in the North, and half were ex-slaves or runaway slaves. They served in more than 160 Colored regiments, but only one-third of the colored regiments ever saw combat.

- 45,000 were born in England. 2% of Union Army soldiers were born in England.

- 20,000 were French. 1% of Union Army soldiers were French (although very few were actually born in France. Most were born in or had roots in Quebec)

- 15,000 were born in Canada

- 14,000 were Scandinavian (nearly all of them were born in Norway, Sweden, or Denmark).

- 7,000 were Italian (nearly all were born in Italy)

- 7,000 were Jewish (many of them were foreign-born)

- 5,000 were Poles

- 4,000 were Native American

- Several thousand were Mexican

- 1 million were Native-born and of British Isles (non-Irish) ancestry. About 40% of Union soldiers were Native-born Americans of British Isles (non-Irish) ancestry.

Many immigrant soldiers formed their own regiments, such as the Swiss Rifles (15th Missouri); the Gardes Lafayette (55th New York); the Garibaldi Guard (39th New York); the Martinez Militia (1st New Mexico); and the Polish Legion (58th New York). But for the most part, the foreign-born soldiers were scattered as individuals throughout units.

For comparison, the Confederate Army was not diverse at all. Nearly all Confederate Army soldiers were of British Isles extraction, and only 3% were foreign-born.

Desertions and Draft Riots

Desertion was a big problem in the Civil War for both sides. The daily hardships of war, forced marches, thirst, suffocating heat, disease, delay in pay, solicitude for family, impatience at the monotony and futility of inactive service, panic on the eve of battle, the sense of war weariness, the lack of confidence in commanders, and the discouragement of defeat (especially early on for the Union Army)), all tended to lower the morale of the Union army and to increase desertion.

In the first two years of the war, there were, by some counts, 180,000 desertions in the Union Army. In 1863 and 1864, the bitterest two years of the war, the Union Army suffered over 200 desertions every day, for a total of 150,000 desertions during those two years. This puts the total number of desertions from the Union Army during the four years of the war at nearly 350,000. Using these numbers, 15% of Union soldiers deserted at some point during the course of the war. Official numbers put the number of deserters from the Union Army at 200,000 for the entire war, or about 8% of Union Army soldiers. It is estimated that 1 out of 3 deserters returned to their regiments, either voluntarily or after being arrested and being sent back.

Of all the ethnic groups in the Union Army, the Irish had the highest number of desertions per capita by far, by some accounts they deserted at a rate 30 times higher than Native-born Americans.

The Irish were also the main protagonists in the famous “Draft Riots” of 1863 (the film Gangs of New York is a dramatization of this event). As a result of the Enrollment Act, rioting began in several Northern cities, the most heavily hit being New York. What happened was that a mob, started by and consiting principally of Irish immigrants, rioted in the summer of 1863, with the worst violence occuring in July. The mob set fire to everything from African American churches and an orphanage to the office of the New York Tribune. The principal victims of the rioting were African Americans and activists in the anti-slavery movement. Eventually the Union Army was sent in and had to open fire to quell the violence and stop the rioters. By the time the rioting was over, 1,000 people had been killed or wounded.